Predicting Enrollment with Aid

Repository Link

Please access the repository here.

Overview

Suggested citation: Posmik, Daniel C. (2022) “Predicting International Student Enrollment by Institutional Aid: A Random and Fixed Effects Approach,” Journal of Student Financial Aid, 51(3) , Article 4.

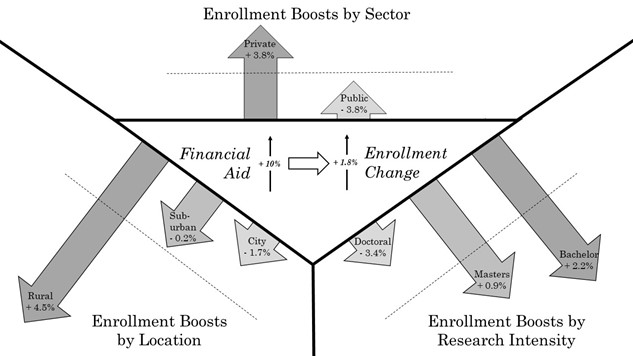

Paper Abstract: Since the fall semester of 2016, first-time international student enrollment (ISEft) has declined at U.S. colleges and universities. This trend disrupts a steady upwards trajectory of ISE\(_{ft}\) rates. Previous research has demonstrated that various political, social, and macroeconomic factors influence the amount of international students studying in the U.S. Exploiting data from the Common Data Set (CDS), I focus on the role financial aid plays as an enrollment predictor for international undergraduate students. A fixed effects model reveals that financial aid is strongly and significantly predictive of ISE\(_{ft}\), yielding a 1.8% enrollment increase per 10% aid increase, all else equal. Interestingly, financial aid is only predictive of ISE\(_{ft}\) if it is awarded in substantial amounts. Extending the work of Bicak and Taylor (2020), I also analyze how the effectiveness of financial aid awards varies within different institutional settings. Random effects regressions reveal that rural, low research, and private universities experience considerable marginal ISE\(_{ft}\) boosts when awarding aid to international students. The findings of this work are primarily directed at institutional leaders who seek to revitalize their institution’s ISE\(_{ft}\) policy. Moreover, these insights may inform local policymakers who seek to incent ISE\(_{ft}\).

Keywords: International Student Enrollment, Financial Aid, Panel Data Regression, Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

Presentation Links

- Presentation at 2022 Cleveland Fed Economic Scholars Program

- Guest Lecture for Dr. Asawari Deshmukh’s International Economics (ECON4040) course

1. The relationship of International Student Enrollment and Financial Aid

Financial aid is an important subsidy for most international students financing their education in the U.S. But to what extent does financial aid predict the enrollment of first-time international students (ISE\(_{ft}\))? To answer this question, I leverage international student aid data from the Common Data Set (CDS). CDS data is the only available source of international student aid data, aside from government data. Notably, CDS data is - somewhat counterintuitively to its name - not centrally aggregated. I spent the better half of an academic year scraping data from individual institution’s websites. Therefore, time constraints necessitated narrowing down the paper’s scope to institutions in the Great Lakes region (OH, MI, WI, IN, IL).

Interestingly, previous literature offers a wealth of insight into the relationship of financial aid and enrollment. The literature, however, only (i) considers certain institutions (e.g., Zhang and Hagedorn, 2018; Bound et al., 2020), (ii) is limited to domestic students (e.g., Dynarski, 2000, 2003; Kane, 2010; Leslie and Brinkman, 1987; Seftor and Turner, 2002), or (iii) is restricted to time-invariant ISE\(_{ft}\) predictors (e.g., Bicak and Taylor, 2020). My paper combines various insight from literature with CDS data in an attempt to understand the role of financial aid as an enrollment predictor for international undergraduate students.

2. Causality

Causal inference or Casual inference - that is the question. Initially, my paper gave rise to a difference-in-differences scenario (DiD) with continuous and multiple-period treatment (henceforth the “cont.-mp” case). Callaway et al. (2021) - the theoretical basis for this paper’s causal inference design - outline five criteria that would allow for a causal interpretation in the cont.-mp scenario:

- Assumption 1 (Random Sampling): The observed data are independent and identically distributed (iid).

- Assumption 2 (Support): There is a control group of units that are general enough to allow for continuous treatment.

- Assumption 3 (No Anticipation / Staggered Adoption): Units do (i) not anticipate treatment and (ii) upon becoming treated with dose d at time t, remain treated with dose d in all subsequent periods.

- Assumption 4 (Strong Parallel Trends): Restricts paths of both untreated and treated potential outcomes such that that all dose groups treated at time t would have had the same path of potential outcomes at every dose.

- Assumption 5 (No Treatment Effect Dynamics/ No Treatment Effect Heterogeneity): Homogeneous behavior of treated units across groups, treatment time, and treatment timing group

Assumptions 1 - 3 are weaker assumptions that can be justified even with observational data. Assumptions 4 and 5, however, are much stronger ones. Specifically, Assumption 5 is where the problem lies in my analysis. In my paper, I consider how changes in total aid predict changes in aggregate ISE\(_{ft}\) at time \(t\) at institution \(i\). In order to rule out Treatment Effect Heterogeneity (TEH), I would have to assume that individual characteristics, such as family income or ability (Dynarski, 2000; Cornwell et al., 2006) are quasi-random across institutions i and time periods \(t\). More generally, I would have to assume homogeneity of the causal response (think: Effect of aid on an individual student) across incoming student classes across all institutions and all time periods. That is simply not the case, and any attempt to spin it that way would have been a poor attempt at embellishing the quality of my data. So, in order to avoid authoring yet another casual inference paper, I decided to reject a causal framework altogether and focus on the value this study delivers as a correlational study. Mainly, it is a valuable tool for institutional decision-makers wondering about “how far” their aid money can go. (Sneak peek into the next section: Pretty far!)

3. Modeling

The general model controls for three variables. The log of cost (since aid is only important when relative to cost (see Bodycott, 2009; Darby, 2015)); the perceived quality of the institution via acceptance rate (see Bodycott, 2009; Darby, 2015; Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002), and finally institutional size via the log of total undergraduate enrollment (see Cantwell, 2019). The variables of interest are the log of financial aid as well as aid concentration - a measure of whether Many students receive little aid or few students receive a lot of aid. The dependent variable is the log of ISE\(_{ft}\).

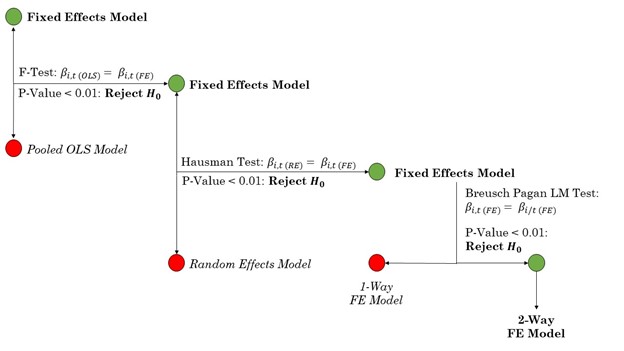

Statistical testing as well as literature led to choose a 2-way fixed effects (TWFE) model.

The results show that both financial aid and aid concentration are the most significant predictors of ISE\(_{ft}\). All else equal, a 10% increase in financial aid yields a 1.8% increase in ISE\(_{ft}\). Done!

… wait …

Didn’t I forget about something? Wasn’t there something about treatment effect heterogeneity? Yes! While it is still impossible to recover causal parameters, I can dig deeper into the heterogeneous nature of aid awards in a predictive framework.

The second part of the paper uses a random effects (RE) model to examine whether aid predictions vary when conditioned on certain institutional characteristics. I examine the interaction of financial aid within the most important (see Bicak and Taylor, 2020) time-invariant institutional predictors of ISE\(_{ft}\): Location (Rural, Suburban, Urban), Sector (Private, Public), and Research Intensity (Low, Medium, High). In a nutshell, those are highly significant ISEft predictors that institutions cannot change (easily). Using a RE model, I interact the log of financial aid variable with a each of those time-invariant characteristics. The coefficient on this interaction term tells us how much more (→ positive coefficient on interaction term) or how much less (→ negative coefficient on interaction term) powerful aid is within this specific characteristic.

The results are fascinating! We can see that rural, low research intensity, and private institutions experience enrollment boosts when compared to their counterparts (note how important a precise interpretation of this RE model is). This suggests that the institutions that generally have the lowest average international student enrollment can profit the most by awarding aid. Especially rural institutions have a high enrollment boost of 4.5% when compared to their suburban and urban counterparts.

4. Results and Implications

These findings - especially the latter ones - have important consequences for institutions. Not only is aid a win-win tool (e.g., Mause, 2009) for international students and universities alike; rural, private, low research institutions can leverage financial aid at a greater efficiency than their counterparts. Since international students bring funding for institutions (see McCormack, 2007; Chellaraj et al., 2008), these institutions can use aid to gain an edge in the higher education industry. In a competitive higher education market, rural, private, low research universities can pursue an internationalization strategy to compete with structurally more desirable institutions (e.g., urban, public, high research).

Lastly, this insight may also be of value for local policymakers. Aid is an effective and reliable tool to attract and retain international talent for policymakers (Douglass and Edelstein, 2009; Li, 2017), creating a means to affect economic development/ growth in certain regions/ industries via universities as intermediaries (Owens et al., 2011). All in all, I conclude that financial aid is a reliable enrollment management tool that prioritizes students, institutions, and economic interests.

5. Addendum for Fellow Statistics Nerds

For me, this paper is interesting for many reasons. However, one of my favorite features is a creative use of the random effects model to shine light on heterogeneous treatment responses from a correlational perspective. This is quite an unusual application of this technique, so I have decided to write this addendum with a detailed explanation surrounding it. Before we get started, please note that any longitudinal data analysis technique I use–i.e. fixed and random effects models–has nothing to do with a claim to causality, regardless of their potentially misleading name.

Generally, a pooled ordinary least squares (Pooled OLS) model takes the form

\[Y = \alpha + \beta \mathbb{X} + {\epsilon}_{i,t}\]where \(\alpha\) is the constant, \(\mathbb{X}\) is a \({p}\times{n}\) matrix of independent variables (\(n\) observations of \(p\) variables), and \({\epsilon}_{i,t}\) is the idiosyncratic error term. Without any causal assumptions, \(\beta\) is ordinary least squares coefficient, pooling all data together regardless of time period and institution. Now, this is where the first problem arises. When dealing with longitudinal data, is seldom the case that pooling data accurately represents reality. There are likely group-specific correlations, i.e. aid awards within certain years or certain universities. Although there may not be across-group correlation, the within-group correlation result in endogeneity that is not accounted for. In simple terms, our pooled OLS model does not explain everything it should!

Now, what can we do? We could account for these within-group correlations by simply removing them before estimation. This is exactly what a fixed effects model does. Mechanically, the fixed effects coefficient $\beta_{FE}$ is obtained by demeaning the pooled estimator by time and institution averages:

\(\bar{Y}_i = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} Y_{i,t}\) \(\bar{X}_i = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} X_{i,t}\) \(\bar{\epsilon}_i = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} \epsilon_{i,t}\)

which are then subtracted from the pooled variables such that

\(\tilde{Y}_{i,t} = Y_{i,t} - \bar{Y}_i\) \(\tilde{X}_{i,t} = X_{i,t} - \bar{X}_i\) \(\tilde{\epsilon}_{i,t} = \epsilon_{i,t} - \bar{\epsilon}_i\)

which finally yield the fixed effects model:

\[\tilde{Y}_{it} = \beta_{FE}\tilde{\mathbb{X}}_{it}' + \tilde{\epsilon}_{it}\]A random effects model takes a similar–albeit not identical–approach to identification. Notably, random effects model is useful when pooling disregards important across-group correlations but two-way demeaning is too drastic. Notably, a random effects model is the middle-ground between a pooled and fixed effects approach. Specifically, a random effects use fixed effects only for the time-invariant differences across entities or groups, while the random effects capture the variation within entities or groups that cannot be explained by the observed covariates. The key differences lies in how the within-group demeaning is handled! – Okay, I understand this a pretty abstract thought, but I guarantee you this going to get clearer when we look at the mechanics of the estimation. Stick with me!!

Rather than demeaning by a “full” average across both time and group (see fixed effects), we only fully demean over time while partially demeaning over group. This looks like this:

\(\tilde{Y}_{i,t} = Y_{i,t} - \textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} \bar{Y}_i\) \(\tilde{X}_{i,t} = X_{i,t} - \textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} \bar{X}_i\) \(\tilde{\epsilon}_{i,t} = \epsilon_{i,t} - \textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} \bar{\epsilon}_i\)

where \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} \in [0,1]\). Immediately observe that when \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} = 0\), we get our pooled estimator because we effectively subtract nothing from it. Similarly, when \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} = 1\) we get our two-way fixed estimator because we demean by the full average! Pretty cool connection, right?

That’s all great so far–but what exactly is this ominous \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda}\)? Where does it come from? Where does it go? Where’d you come from Cotton Eye Joe? Just kidding, but seriously, bear with me again as it gets a little abstract again:

\[\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} = 1 - \sqrt{\frac{\textcolor{red}{\sigma_{\epsilon}^{2}}}{\textcolor{red}{\sigma_{\epsilon}^{2}} + \textcolor{green}{T}\times\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}}}}\]Let’s peel this monstrosity back–piece by piece. \(\textcolor{red}{\sigma_{\epsilon}^{2}}\) is simply the variance of our idiosyncratic error term \(\epsilon_{i,t}\). Now, \(\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}}\) is the variance of an unobserved term \(\delta_i\) which is the across-group error term. Theoretically, we can also combine \(\textcolor{blue}{\delta_i} + \textcolor{red}{\epsilon_{i,t}}\) into a composite error term, but that is simply a preference of notation. Just understand that \(\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}}\) measures variance only across groups and \(\textcolor{red}{\sigma_{\epsilon}^{2}}\) across both groups and time. The term \(\textcolor{green}{T}\) signifies the number of time periods and functions as a weight to our across-group variance term.

In this arrangement, \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda}\) gets closer to 1 (“demeans more”) when either \(\textcolor{green}{T}\) and/or \(\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}}\) become large. The random effects estimator demeans less (closer to 0), when those terms are low. That means the random effects estimator “punishes” across-group variance. Simply put, it feels the need to subtract more if the groups are not similar to one another, or if the variation amongst the groups is large. If that is the case, it assumes that random variation within the groups is larger. This is also where the estimator derives its name from.

Other details, like the functional form of \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda}\) (e.g., why is there a square root?), are also important. However, explaining that would require me to go into the asymptotics of the random effects estimator and that is a little beyond the scope of this addendum. The most important take-away from the section is that you understand what the different variance components mean. To make this more tangible, here is a list of corrolaries that significantly improved my understanding of the random effects estimator:

- Consider \(\textcolor{green}{T=0}\): This Makes \(\textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} = 0\). This makes the random effects estimator equal to the pooled estimator. This makes sense because zero time periods is analogous to pooling everything together (i.e. we don’t differentiate between time periods)

- Consider \(\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}} = 0\). This also makes the random effects estimator equal to the pooled estimator. This time, zero variance in the across-group variance means that there is practically no across-group difference. This means that we pool everything across groups – Ta Da!

- Consider \(\textcolor{red}{\sigma_{\epsilon}^{2}} = 0\). Again random effects estimator equals pooled estimator. If there is no variance across either time and groups, it follows that there is no variance in neither group nor variance. We pool again!

- Putting all this together, it follows that we have a random effects estimator of and only if \(0 < \textcolor{orange}{\Lambda} < 1\). The edge cases of a random effects estimator, are a pooled estimator and a fixed effects estimator for \({0,1}\) respectively.

Phew–good job! If you’ve read that far, you have a very solid background in pooled, fixed effects, and random effects estimators. Now, let’s proceed to the meat of this section: How I used the random effects estimator to estimate correlations within time-invariant settings.

The fixed effects estimator is simple and effective–making it a popular tool amongst applied empirical researchers working with panel data sets. However, one of its main strengths can also be a major drawback. Recall that a fixed effects estimator demeans fully over time, aka it removes everything within a group that doesn’t vary over time. This makes it impossible to interact time-invariant variables with a fixed effects estimator because, well, it would just be removed! Luckily, we learned that we have a tool at our disposal that functions similarly to the fixed effects estimator, but doesn’t fully demean across both dimensions.

I used a random effects model to analyze how the correlation between financial aid and international student enrollment changes within time-invariant institutional settings. This is really important because there is strong evidence (see, Bicak & Taylor 2021) that time-invariant institutional characteristics, e.g., research activity, location, and sector, are amongst the most important predictors of enrollment. My random effects specification interacts a categorical dummy variable for each of those time-invariant institutional characteristics with the financial aid variable.

By using the the across-group variance \(\textcolor{blue}{\sigma_{\delta}^{2}}\) I can still account for the across-group differences without having to fully demean across them. Isn’t that cool?

The coefficients on these interaction terms showed the marginal differences in enrollment changes across institutional settings. Summa summarum, this is a sneaky way to circumvent the principal weakness of the fixed effects estimator!

P.S.: I want to thank Ben Lambert whose YouTube series made summarizing key concepts exponentially easier.